From French Trotskyism to Social Democracy. “68, et Après. Les héritages égarés. Benjamin Stora” Review.

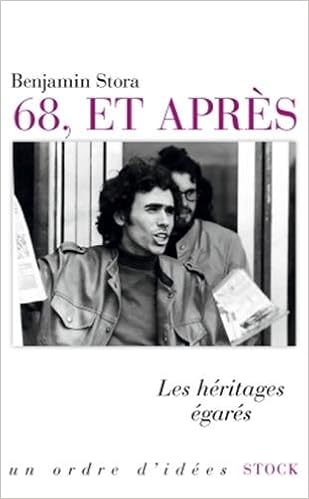

68, et Après. Les héritages égarés. Benjamin Stora. Stock. 2018.

The present wave of strikes and student protests in France have drawn comparisons with the stoppages and protests against the 1995 ‘Plan Juppé”. This reform of state health and retirement insurance, including the railway workers’ pensions, struck at the heart of the French welfare state. There is a strong resemblance between this social movement and the opposition of public sector workers and undergraduates to President Macron’s efforts to ‘modernise’ the French rail system and Universities, (Le Monde 28.3.18).

Others, notably in the English-speaking left, have evoked the spirit of ’68. Some on the French ultra-left, who might be considered to inherit a fragment of the soul of that year’s revolts, state in Lundimatin, that they “do not give a toss” (on s’en fout) about the anniversary of the May events. (Nicolas Truong. Le Monde 15.3.18) Rather than commemorate, or organising Occupy or Nuit Debout style alternatives, they will be busy tearing into Macron, speaking truth for the Coming Insurrection. (1)

That section of the far-left is, of course embroiled in the continuation of the Tarnac trial. Others from a close milieu are involved in resisting the clearing of the last self-organised squats at Notre-Dame-des-Landes.

Benjamin Stora’s 68, et Après is written from a standpoint both familiar internationally, the fall out from the crushing defeat of the French left in last year’s Presidential and Parliamentary elections, and one far less well-known, the history of a section of Gallic Trotskyism, the ‘Lambertists’.

It is also an autobiography, from his origins in as a North African Jews, his education, his many years of activism, and university career. Stora has produced important studies of French Algeria, the war of liberation, and post-independence Algerian history, including the exile of its Jewish population. There is a finely handled account of the tragic death of his daughter in 1992. Stora’s commitment to study the Maghreb did not wholly override political commitment. Opposition to the Jihadists – and be it said, the Military – during the 1990s civil war in Algeria – led to Islamist intimidation. After a small coffin inscribed with words from the Qur’an, and a death threat addressed to Unbelievers, Jews and Communists arrived at his home the historian was forced to leave France and spend time in Vietnam, the occasion for further fruitful reflection on post-colonial societies.

Generation 68

Stora argues that the notion of a 68 ‘generation’ (popularised in Hervé Hamon and Patrick Rotman’s landmark 1987 book of the same name) is misleading. He notes the two volumes lack of attention to his own tradition. A full-time activist in the 1970s the former Lambertist suggests, notably, that his own tendency, whose internal regime and (to put in terms this reviewer, whose background is amongst its left-wing rivals) stifling narrow-minded morality (up to hostility towards feminism and gays), was also part of the post-68 radical movement. This is indeed the case, although not many beyond their circles had a taste for denunciations of “petty bourgeois deviations” and ritual revolutionary socialism. (Page 31) Those familiar with the history will suspect the reason for their absence (one Index reference to Lambert) in Génération. That is, the Lambertists’ call during one of the most celebrated moments of 68, for students to disperse from the Boulevard Saint-Michel rendered, “Non aux barricades” and to go to the workers at Renault, Michel (Night of 10-11th of May). (2)

The history of this highly disciplined current, around the figure of Pierre Lambert (real name Boussel) in 68 known as the Organisation communiste internationaliste (OCI) is long and, to say the least controversial. But their imprint is not confined to the fringes. Lambertists have played an important part in the recently governing Parti Socialiste (PS). Amongst one-time members are the former Prime Minister, Lionel Jospin, and the ex-Socialist leader of La France insoumise, Jean-Luc Mélenchon.

Stora, like PS General Secretary until last year, Jean-Christophe Cambadélis, was part of a several hundred strong Lambertist faction which joined the PS in 1986. Cambadélis, in his most recent book, Chronique d’une débâcle (2017) makes passing reference to a Trotskyist past (his ability to spot sectarian manoeuvres is undiminished). L’après 68 gives an extensive account of the organisation, from weekly cell meetings, whose minutes were rigorously kept and transmitted to the party HQ, to their exploits in the student unions and ‘mutuals’, friendly societies which play an important part in assuring student health and other forms of insurance.

Stora’s La Dernière Génération d’Octobre (2003) covers, he remarks, the post-68 culture and politics of his time in the OCI. The present volume gives probably more attention to the way in which his faction from this generation moved from full-time Lambertist activism, often paid for by one of the fractured French student unions, the UNEF-ID, in some cases by Teachers’ unions) into the late 1980s Parti Socialiste. Going from a clandestine fraction, led principally by Cambadélis, suspicious of surveillance by a group whose way of dealing with dissidence was not too far off the British WRP’s, they broke with Leninism. This was not just in opposition to the vertical internal regime, and the reliance on the “transitional programme” but, as they saw it, to establish a left-wing force within the democratic socialist spectrum represented in the post Epinay PS.

A deal reached with Boussel, to avoid the violence and rancour traditionally associated with splits, was soon behind them. Despite the author’s best efforts it fails to disperse the suspicion, which those of us who are, let’s just say, not greatly fond of their tradition, had that some kind of arrangement also took place between Lambert and the PS itself over their entry into the party. (3)

Inside the Parti Socialiste.

An organised PS current, Convergences socialistes, with all the self-importance that afflicts parts of the French left and academics, they numbered around 400 members. Of these a few moved into open professional politics. As a coherent body it is hard to find much trace of them in the shifting alliances within the PS, although one may find some remaining allies of Cambadélis as he clambered up the party hierarchy.

Just how adept former Lambertists could be in the PS game is registered by Stora’s portrait of an individual who had joined the PS some years before, Jean-Luc Mélenchon. The present chief of La France insoumise, with a seat in the senate’s august halls, shared a wish create a new vanguard with his own tendency, the ‘Gauche socialiste’. He was equally marked by burgeoning admiration for François Mitterrand. This did not go down well. Stora recalled the President’s role in the repression of Algerian insurgents…(Page 49 – 50). In a critique of Mélenchon’s present politics, Stora draws comparisons with the old Communist Party’s wish to impose its hegemony on the left, and keep its activists preoccupied by frenetic activism (Pages 150 – 153).

The root cause of the present débâcle is Parliamentary left lost touch with the people, part of an autonomous political sphere. The history of how a section of the radical left made the transfer from revolutionary full-timers to PS MPs and functionaries (and a galaxy of dependent positions) is not unique. It could be paralleled on a smaller scale by the career of the UK Socialist Action in Ken Livingstone’s London Mayor administration. The insulated, amply rewarded, lives of politicians, is, it is often said, one of the causes of the break down of the traditional French parties of right and left. Stora does not neglect his own current’s involvement in the student mutual, MNEF, corruption scandals, (Page 129). Whatever remains of the difference between ‘revolutionaries’ and ‘reformists’ fades into the distance faced with a managerial-bureaucratisation enveloping the current. The same processes, born of their reliance on union positions and opaque funding are not without effects on the remaining loyal Lamberists in the le Parti ouvrier indépendant (POI) , and their split, the Parti ouvrier indépendant démocratique (POID).

After 68?

Après 68 is above all is a rousing condemnation of the “neo-nationalism” grounded on French “identity” and fear of “decline”. This, from the 2005 European Constitution Referendum (which divided the French left including, Stora notes, some on his section of the radical left) dominates French politics, left and right, up to its presence in the ‘synthesis’ offered by President Macron. French political space, he observes, no longer dominated by the Parti Socialiste, is open. From 1968, writes both the historian and left winger he keeps two passions, for History (the source of his productive career) and the internationalist defence of those without rights, the desire for a common human civilisation. Staying hopeful that hopes for a new world have not been extinguished, L’après 68 is full of important messages from an old one.

*****

(1) See: A nos Amis. 2014. Le Comité Invisible 2014. Page 64. “Voilà ce qu’il faut opposer à la « souveraineté » des assemblées générales, aux bavardages des Parlements : la redécouverte de la charge affective liée à la parole, à la parole vraie. Le contraire de la démocratie, ce n’est pas la dictature, c’est la vérité. C’est justement parce qu’elles sont des moments de vérité, où le pouvoir est nu, que les insurrections ne sont jamais démocratiques.”

(2) Pages 467– 469. Les Trotskyistes, Christophe Nick. Fayard. 2002.

(3)See for example, the series in le Monde by Nathaniel Herzberg in 1999 on the subject commented on here: De la « génération » comme argument de vente… A propos d’une série d’articles sur la « génération MNEF ».

Written by Andrew Coates

April 10, 2018 at 1:10 pm

Posted in Anti-Fascism, Europe, European Left, French Left, French Politics, Gay Rights, Human Rights, Labour Movement, Left

Tagged with European Left, French Left, Jean-Christophe Cambadélis, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, Lambertists, May 68, Parti Socialiste

2 Responses

Subscribe to comments with RSS.

Dear Andrew, I did not read this book but the first one which uses the official false statistics of the OCI as truthful numbers. Just this fact disqualifies him as a historian of this own political current. I can only advise people who read French to read Karim Landais’s book about the OCI/PT the only book which includes more than 200 pages of interviews from former members and leaders of this political current. This could be a good antidote to Mr Stora’s strange way of telling his story and history…. Yours Yves http://mondialisme.org/spip.php?article1944

Yves Coleman

April 10, 2018 at 6:26 pm

Thanks, lying about membership numbers (demo numbers as well), is an old Trotskyist tradition.

I hesitated about the figure – the first paragraph on the split avoids it – but he does say that.

I would indeed have found 400 remarkably big, and I had some contact (not friendly I hasten to add) with the Lambertists during this period.

They had a maximum 200 on the demos against the Devaquet reforms in 1986 and probably not a lot more on the march following the death of Malik Oussekine.

Andrew Coates

April 11, 2018 at 10:27 am